In this episode of “The M-Files” we present an analysis of a portion of the conversation between Russell Brand and Jordan Peterson on Brand’s talk show, “Under the Skin #52.” The two offer their unique perspectives on the 12-Step program (which began with Alcoholics Anonymous) that brings up many brilliant insights.

There are direct connections between the 12-Steps, the kabbalistic path of the Tree of Life, and interesting parallels to the Matrix story and the Path of the One. All of these reflect a process for humans to be freed from bondage to a skewed perspective on life – “a prison for your mind.”

We suggest first reading the three template articles in our Knowledge Base and the previous article in The M-Files called, “The 7 Habits and the Matrix,” as prerequisites to this discussion.

We add our commentary throughout the transcript below in italics.

Our section of the transcript begins at the 14-minute mark of the video. < CLICK!

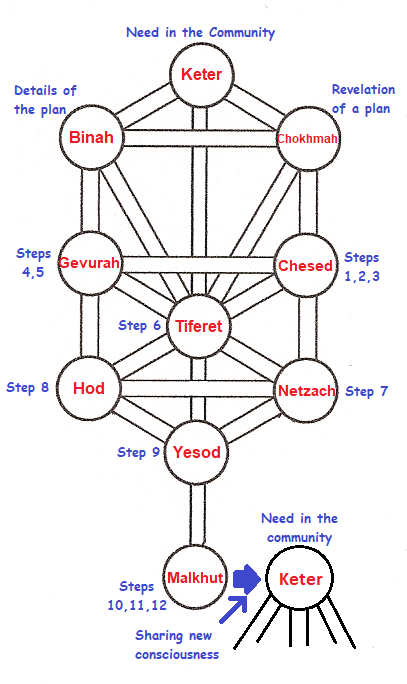

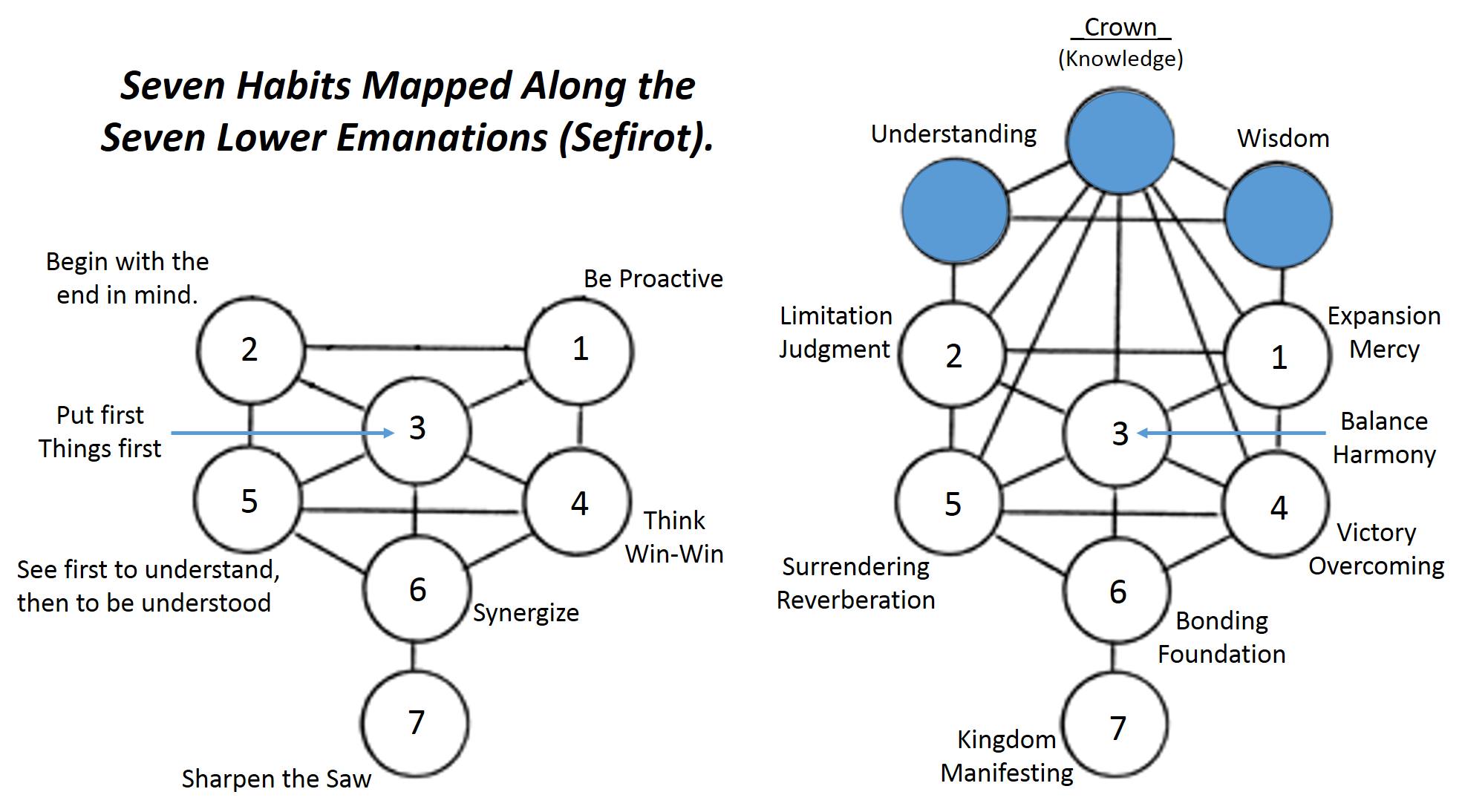

As with Stephen Covey’s “7 Habits of Highly Effective People,” the 12-Step program is a model that reflects the path of repair of one’s attributes that is based on the seven emanations of God that we deal with in our present existence. These seven are called the ‘middot’ which means ‘measures’ or ‘values.’

Note that as in our M4H Knowledge Base, we use the terms; emanations, attributes, sefirot, and middot, interchangeably.

The 12-Steps also follow the same pattern as the 7 Habits, broken down into:

- A group concerned with focus on improving self

- A group concerned with relationship to others

- Continual improvement and reaching out to help others

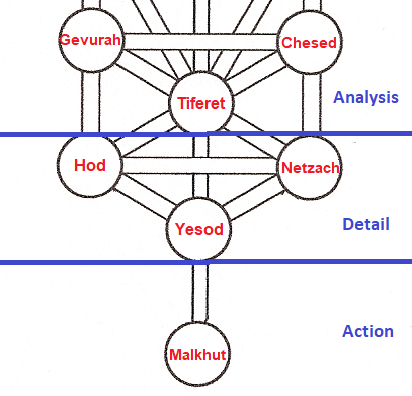

Specifically, with the 12 Steps, we have the first six related to analyzing one’s self via taking a personal inventory and initiating a change of mindset.

This is followed by the next six, which are concerned with forming a detailed plan and putting everything into action for both self-change and making amends to anyone we may have harmed, when and however appropriate.

The process does not end with the individual. Empowered with a new consciousness, one on the path of recovery can reach out to those needing similar help, both completing and renewing the circuit.

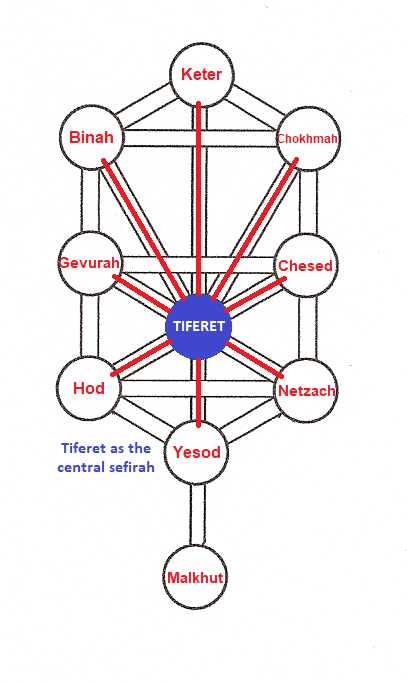

Thus, the Malkhut (‘end’) of one reality becomes the Keter (‘beginning’) of the next. This is outlined on the Tree of Life diagram as shown. Note the ‘path’ descends in a right then left manner (like a lightning bolt). We give greater detail in an introductory article in the Matrix4Humans Knowledge Base.

Introduction

We begin with Russell Brand (RB) introducing the topic of the 12-steps (at the 14-minute mark). For context, both men have authored books that relate to this. Peterson’s book is called, “12 Rules for Life” and came out in 2018. Brand wrote “Recovery: Freedom From Our Addictions,” which was released in 2017. Both books are highly recommended by M4H.

An interesting point, regarding this first section of their discussion, is the reference to ‘community’ made by Brand. As with the 7 Habits, our path to ‘self’ leads to and must involve, relationships with others as well as a spiritual connection. The two go hand in hand with regard to rectification and healing.

RB: I want to talk to you a bit about the 12 Steps, and the model for handling addiction. I’ve written about myself in my book, “Recovery,” because I want to see what you think of it. 12 Steps have anonymous fellowships. If I were to belong to them, I wouldn’t be able to say I belonged to them, without breaching their code of anonymity. But what’s positive about this approach to addiction is—as we have discussed off mic—it creates community. Other people that have got a similar endeavor—in fact, it was Jung who identified this solution. He said that people who have got chronic addiction issues will struggle to change, unless they have a spiritual realization of some kind and the support of community.

JP: The spiritual realization component—that’s actually supported by the relevant addiction literature. One of the classic cures for addiction is spiritual transformation. The hardcore scientists have laid that out as a reality in the addiction literature.

RB: I agree, because they use more secular language around that, as spiritual transformation could just be a change of perspective, a renewal.

JP: A radical change of perspective.

RB: Typically, from my experience, that’s from a self-centred view, a self-obsessive view, about getting your own needs met—a solipsistic, narcissistic perspective, about “life is just this adventure where I go around trying to accumulate and accrue,” to, “oh, wow—I’m here to be of service.” That’s the transition, microscopically. But in addition to community—like having connections between one another—the 12 Steps themselves, I think, are an interesting model for transformation, and shouldn’t be overlooked. In fact, what my book was about—could that method be transposed to anybody who’s interested in change? I wanted to talk to you about that, to get your perspective.

Note: Brand’s comment regarding one’s perspective, changing from egocentric to the understanding that we are here to serve others, is the major, hidden lesson of the Matrix story as is discussed in our Knowledge Base. As we explain, the character of the Merovingian is representative of Brand’s description of someone entirely focused on accruing things for themself. As the Oracle stated, “What do all men with power want? More power.”

CHESED

Step 1. We admitted we were powerless over alcohol—that our lives had become unmanageable.

Step 2. Came to believe that a Power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity.

Step 3. Made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understood Him.

The first three of the 12 Steps are conflated into one by Peterson (as Brand notes). They are all aspects of Chesed. There is nothing ‘tangible’ or directly related to the other Steps (or people) yet. Nor are we analyzing in any detail. That comes next with Gevurah/Judgment in Steps 4 and 5.

As with the 7 Habits and seven middot, the first step is to be pro-active, even without knowing details of “where this will take you.” This is the essence of Chesed which is “kindness without need for a reason.” It connects to the aspect of ‘faith’ which is rooted in Wisdom/Chokhmah above it. (See ‘Tree of Life’ diagram.)

In kabbalah, Wisdom/Chokhmah relates to the past – everything up to the very moment we make this decision. In the Matrix, this is symbolized by all of the screens in the Architect’s lair, which displayed the history of mankind and Neo’s own life.

Chesed involves all three aspects of human nature which are reflected in the first three of the 12 Steps:

-

- There is a direct physical aspect to the first step regarding the impact in our life that alcohol has.

- Then we have an emotional connection made in the hope of something greater than ourselves and our situation.

- Finally, there is an intellectual decision made to connect to this higher reality.

In terms of our souls, we exist simultaneously in ‘four words of existence’ – physical, emotional, intellectual and spiritual. Methods such as the 12 Steps and 7 Habits help us understand this and better negotiate our path in life.

All of the associated attributes of Chesed are found in the character of Morpheus in the Matrix. Morpheus acts according to the principles of his ‘belief’ throughout the three movies. The importance of his principles/belief is expressed by the Oracle in her statement regarding Morpheus when she first met Neo – “Without him we’re lost.” (Without belief/principles, we are ‘lost’ – unable to find the path.)

Neo’s own “first Steps,” reflect the three mentioned above in his first discussions:

- When he first meets Morpheus, they discuss Neo’s dissatisfaction with his life. Neo reveals, “I don’t like the idea that I’m not in control of my life.” This assertive view has a problematic aspect to it, namely, “hanging on” for the sake of being in control. Morpheus does not disagree with Neo’s distorted views, confirming then bonding by replying, “I know exactly what you mean. Let me tell you why you’re here.” He then begins to introduce Neo to the idea that it is his view of reality that is the real issue and that there is a path that will enable him to understand and overcome this.

- Later, Neo is introduced to the concept of a “higher power” (the Oracle) that can help him understand things. (Oracle = Binah/Understanding in kabbalah as we explain.) In the car ride over, Trinity reminds him that the Matrix (his false view of reality) cannot “tell him who he is.” When he asks her, “But an Oracle can?”, Trinity correctly replies, “That’s different,” as it is critical for Neo to find his own path. There is but one Higher Power, and the ‘Steps’ to “get there” are defined, but the application of those Steps remains individualized.

- The Oracle reinforces this at their first meeting, when she tells him he is not yet ready – as she perceives Neo is still holding on to his flawed perspective and not yet willing to “let go and let G0d.” The advice he received on the way in, “Do not try to bend the spoon … it is not the spoon that bends, it is only yourself,” is at the heart of his change of perspective. This goes back to Morpheus’s words to him, mentioned above. This briefly appears to be a setback for Neo, but Morpheus wisely tells him that, “What was said was for you and for you alone.” Neo will have additional choices to make – as the Oracle cryptically spoke regarding saving the life of Morpheus versus his own.

RB: The first step is acknowledging that you are powerless over your addiction and that your life has become unmanageable. Just admitting, “I don’t want to be in this situation.”

JP: OK. There’s two parts to that admission. One is that you’re in trouble… I guess there’s three. “You’re in trouble, and it’s serious. Things could be better. And you don’t have the wherewithal, at the moment, to make them better.” The thing that’s interesting about that is that there’s a kind of radical humiliation and humility that goes along with that. So you say, “I have a problem, and what I know, at the moment, isn’t sufficient to solve it.” Great, because now you’ve opened yourself up to the possibility of learning something. You say, “I don’t know enough to fix this.” It’s like, “OK, well, you could learn.” One of the things that’s so interesting about people is that, if they decide they have a problem, and they also notice that they could learn, the probability that they will learn goes way up.

RB: That’s very interesting. You’ve actually conflated the first three steps there, in your analysis of the first one. The first one is admission that there’s a problem. The second one is recognizing that things could improve—coming to believe that a power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity. The third one is to make a decision to turn our life and our will over to the care of God, as we understood God.

JP: We can talk about that from a secular perspective, and say, “well, there’s a higher order moral principle that needs to be brought into the situation.” And you sort of described that, right at the beginning of the question. You said, “well, from a psychological perspective, partly what you do, when you move from an addicted state, is move from a viewpoint of the gratification of immediate desire—and maybe the accumulation of things as a marker of success—to the notion that, no: you actually have a higher purpose, and that higher purpose might involve being of service.” That could be of service to yourself—which means you wouldn’t be addicted anymore, because that’s not a good way of being in service to yourself—and to the broader community, however you might define that. That’s a higher-order purpose. It can integrate your motivations at a level that doesn’t leave you at the whim of impulse. That’s the purpose of a higher-order motivation. OK, so we’ve got three.

Peterson’s statement, concerning a “higher-order moral principle,” closely relates to Stephen Covey’s “principle-centered life.”

GEVURAH

Step 4. Made a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves.

Step 5. Admitted to God, to ourselves, and to another human being the exact nature of our wrongs.

The idea of ‘searching’ and ‘inventorying’ are aspects of Gevurah – Judgment, on the ‘left side’ of the kabbalistic Tree of Life diagram. This parallels Habit 2 of Covey’s 7 Habit, “Begin with the end in mind,” which is grounded in the same aspect of Gevurah/Judgment which stems from “Understanding,” which is Binah above it.

Gevurah is also the related concept of restriction (‘tzimtzum’) where a flawed view of reality is ‘restricted’ (by us and/or God) in order to make room for a more correct level of understanding. It is a fundamental concept in kabbalah that every spiritual advancement is preceded by a restriction/tzimtzum. You cannot ‘choose’ if there is no ‘place’ for ‘other’ to exist.

In the Matrix, this is what lies behind the Oracle’s statement, “We can’t see past the choices we don’t understand.” In kabbalah, ‘understanding’ and ‘freedom’ are equivalent terms.

Ironically, it is Agent Smith who continually provokes Neo into higher levels of understanding. Smith represents Gevurah/Judgment, ‘descends’ from Binah/Understanding (the Oracle) above it, on the restrictive left side of the Tree of Life. The attribute of Gevurah within us functions in this manner.

Peterson explains these steps as a ‘diagnostic’ tool. This also relates to the Oracle (at Binah/Understanding) who was explained by the Architect as, “an intuitive program, initially created to investigate certain aspects of the human psyche.”

This is a very short section – ironically indicative of the restrictive aspect of Gevurah. (1)

RB: Yes. That’s the first three. It’s to get you to that position where you’re willing to change, believe in the possibility of change, and accept help in order to achieve that change. The fourth and fifth steps are about inventorying—this is where the 12-Step Program becomes a fusion of spirituality and psychoanalysis, because the fourth step is like a four-column method, where you write down a list of all your resentments in your life: your childhood resentments, your resentments against the government, people you work with. You write it all down, and it’s a diagnostic tool where you identify what it is in you that doesn’t like that. And also, interestingly—in 12-Step theology, let’s call it—it says that, “any time that you are personally disturbed, you have to take responsibility for it, to a degree.” There is something in you that’s being [inaudible].

JP: Yes, you should at least ask yourself that question: “is it me, or is it the world?”

RB: Yes.

TIFERET

Step 6. We are entirely ready to have God remove all these defects of character.

We now proceed from the shortest section (Gevurah) into the longest – Tiferet. As the central emanation, Tiferet is highly complex. It’s no coincidence that the discussion between Brand and Peterson goes into great depth here, exploring a number of areas, before continuing into the direct Steps that involve our interactions with other people.

Tiferet means ‘beauty’ in terms of harmony. In addition to being the balance of Chesed and Gevurah to the right and left, as the ‘central’ sefirah Tiferet also ‘stands in’ as representing the group, which makes up the “image of God” that we are made in (Gen. 1:27). Thus, Tiferet is the specific emanation that is seen as pulling us toward God, as reflected in this one of the 12 Steps. (2)

As Tiferet represents the entirety of the group, taking in all perspectives, it is also called the “Sefirah of Truth.”

Once we proactively choose to act (through the first three Steps) and after taking the judgmental action of self-inventory (in Steps 4 and 5) we come to this critical moment of putting our trust in God.

This parallels Stephen Covey’s 4th Habit of “Put First Things First,” which as we have shown aligns with Tiferet in our 7 Habits article.

In the Matrix, Tiferet is the state of harmony and connectivity attained by Neo as he moves along the central Path of the One in each of the three movies. This is the balance between Morpheus on the right (whose beliefs “do not require” anyone else to believe as he does) and Agent Smith (the opposite aspect of judgment) on the left. It is also the connection between the two ‘females’ – Trinity ‘below’ (the connection to ‘community’ within the Matrix) and the Oracle ‘above’ (the connection to the Source) as we explain in our Knowledge Base.

JP: Well, let’s consider first the possibility that it might be—I wrote about that in the sixth Rule: “put your house in perfect order.”

RB: Yes, yes. In fact, I did a truncated and somewhat more linguistically explicit, expletive-laden version of the 12 Steps, and I’ve got your 12 Rules for Life, here. They don’t necessarily correlate… Say your first one, “stand up straight with your shoulders back.” That’s a great chapter, I think. I love the lobster stuff, and the ancient, timeless—almost roots—of hierarchy.

JP: Yeah.

RB: And the chemicals that are at play—what’s happening when we talk about self-esteem. The sixth one, “set your own house in perfect order before you criticize the world”—steps four and five, in the 12-Step Program, deal with that: Inventory what’s going on in your life. Inventory what your baggage is, in your own personal narrative.

JP:

It’s very practical. Let’s say you want to fix up your house—which is, actually, quite a lot like fixing yourself up, and which is quite a common dream metaphor. The first thing you want to do is go around and see what needs to be fixed. The interesting thing about that is akin to what comedians do: comedians look at a problem and rise above it, and make a joke about it. As soon as you’re willing to admit that you have a problem, then you’ve immediately contacted the part of yourself that’s at least strong enough to admit that you have a problem. The act of admitting the problem is actually the first step to solving it.

RB: Yes.

Interestingly, in the Matrix, Agent Smith’s comments about humans acting like viruses ruining their own world, relates to this point.

On the one hand, Smith acts “within the Matrix system” in the first movie, functioning to preserve the status quo by enforcing a highly negative view of humans that he claims will not change. “We (the Matrix system) are the cure” he states – promoting the ‘addiction.’)

On the other hand, it is by way of ‘Smith,’ as Gevurah – the “agent of change” (Steps 4 and 5) that Neo and others are able to escape the Matrix. This is the false view of reality that the 12 Steps enables escape from.

The same attribute of judgment that we condemn and restrict ourselves with, must be rectified to become the power it was intended for – enabling us to heal by moving closer to God.

This is another ‘secret’ in The Matrix as Neo utilizes Smith’s power to repair the Matrix at the end of the 3rd movie. Of course, this is only a step in the direction of true freedom – which will come in the 4th film.

JP: It’s an optimistic step, because you might say, “oh, my God—I can’t admit that I have a problem, because what if I can’t solve it?” Well, exactly—then, maybe, you won’t admit to it. If you do admit to it, you’re simultaneously admitting to the possibility that you could solve it.

RB: Yes.

JP: And then it can actually become something that’s optimistic.

RB: Yes.

JP: You can say, “my life is horrible. I’m doing 50 things wrong. Well, great! I can fix those things. Then, maybe, it won’t be so horrible.”

RB: The admission itself demonstrates progression and possibility for further progression.

JP: Exactly. That’s why humility is always stressed in great religious traditions. Humility is precisely that. You have to look at why you’re not so good.

RB: Yeah.

As taught in kabbalah, ‘humility’ is the ‘first gate’ of advancement at every level. Humility is not having low self-esteem – it is about having a precise understanding of where you really stand. We see this throughout their discussion.

JP: That has to break down your pride, to some degree, and your arrogance. That’s great, because if you break down your pride and your arrogance, then you’re primed to learn, and you can solve your problems. It’s a bit crushing, to begin with, because you might think, “oh, my God—there’s a lot of things wrong with me.”

RB: Yes.

JP: But then, at least, you’re on the road to fixing them.

RB: My personal journey of recovery has been like a kind of death. When I was 27, it was like the death of the drug addict self. That guy died.

JP: That’s funny, because I told Tammy when we were coming here today that, when you were 27, you made the decision to live. I knew it was 27, because celebrities who are sort of on fire die all the time at 27, because they don’t make that decision. They don’t decide that they’re going to take that final step into maturation. They want to hold on to that Peter Pan thing, that possibility.

RB: Pluripotent.

JP: You bet. Exactly that. They want to hold on to that. You can’t hold on to that and live.

RB: Yes, and then there’s a further death. I’m noticing now, in my early forties, that I’m now at the midway point, in a sort of Dante-esque way. Now I’m moving towards the grave, and now there’s a different kind of alertness emerging. Back to Step four and five, this process of inventorying. After you’ve made an inventory and you’ve honestly and openly put down everything: incidents of child abuse, things you’ve said to other people—once you’ve been willing to inscribe your shame, then you tell another person, a person that you trust. In the original literature, it says it could be a cleric, a doctor, or whatever. In 12 Steps, it’s typically a mentor figure. But that’s the role of confession, which is obviously a huge part of psychoanalysis. The part in your book that I think this pertains to is when you talk about the dragon. You said there was that kids book that you read, about the dragon getting bigger and bigger if it’s not identified. I think four and five are somewhat like that.

JP: Yeah, and part of the point of that kid’s book is that, as soon as you turn around and look at something, it tends to shrink. That’s partly because—imagine you have a memory that you won’t confront. Well, there’s something in that memory that’s terrifying, and that means that it’s sort of associated with everything else that’s terrifying. It’s a horrible memory, but then, when you turn around and look at it, you think, “yeah, it’s horrible; but it’s horrible in this precise and defined way.” That takes it away from all the other potential horrors of it. It starts to shrink it, right away. It also makes you into the thing that can turn around and look at the horror, which is a real positive transformational act, on your part.

There’s a scene at the end of the first Matrix movie where Neo is alone in the subway station and chooses not to run away from Smith but to confront him. His choice goes back to the truth Morpheus had told Neo (which relates to what Peterson says about “horrible in a precise and defined way,”) when he said of the ”agents’:

There’s a scene at the end of the first Matrix movie where Neo is alone in the subway station and chooses not to run away from Smith but to confront him. His choice goes back to the truth Morpheus had told Neo (which relates to what Peterson says about “horrible in a precise and defined way,”) when he said of the ”agents’:

“Their strength and their speed are still based in a world that is built on rules. Because of that, they will never be as strong or as fast as you can be.”

This can also be understood as Neo applying Covey’s 4th Habit (related to Tiferet) of “putting first things first.” In this case the “truth” (=Tiferet) that he can overcome any negative ‘agent’ seeking to enable the false system of the Matrix (i.e. addiction, etc.)

RB: That’s true—that, somehow, being prescriptive and being specific, the problem becomes manageable. Otherwise, it’s limitless in its potential. It becomes apocalyptic, in the end. What’s the worst thing that’s coming? I could be destroyed, and everyone I love could be destroyed, and earth itself could be destroyed. Until you say, “well, actually what this is, is that you feel inadequate, because you weren’t role-modelled correctly.” “Well, all right. Maybe I can take care of that.”

As Morpheus spoke: “I didn’t say it would be easy, Neo. I just said it would be the truth.”

JP: Right. It’s still bad, but it’s not everything. You phrased that exactly right: without that attentive delimiting, it becomes apocalyptic. That’s a very, very old idea. One of the things that happens in the Mesopotamian creation myth, the Enuma Elis, is that the gods are the offspring of chaos. That’s a good way of thinking about it. They become very careless, and they destroy their category system—they destroy their father, essentially, and chaos comes flooding back. That’s what happens to people who aren’t looking at things and delimiting them properly. They become apocalyptic, and do them in.

RB: But sometimes, in mythology, there is the positive confronting of the God, e.g. Prometheus. So sometimes we need to steal the fire; sometimes we need to challenge these orthodoxies, don’t we?

JP: Yes, absolutely. Part of the death that you’re describing is actually the confrontation with a form of tyrant. Your previously-addicted self was the tyrant over your emergent self.

RB: Yes.

JP: And so it’s an internal tyrant, and you said it was predicated on a false value system—that’s a false set of gods, essentially. So you had to confront that; that is a kind of death.

Brand and Peterson speak of, “challenging of God, confronting orthodoxies and false value systems. ” This is also reflective of Tiferet, the sefirah of ‘truth.’

RB: I also think that addiction, or addictive tendencies—and I don’t mean as severe as chemical dependencies. All forms of addiction are a kind of self-constructed formaldehyde, to preserve you in a state of trauma. The trauma is acknowledged; no means to navigate trauma are present, because of the isolation, because you have no mentor. You have no doctrine, you have no community. So addiction steps in: “This is how I will preserve; this is how I will not die.” Notice there is a habit, a repeated pattern to sustain you—a holding pattern—so that you don’t die. There is no way out; there’s no guide; there’s no path. You’re just in the forest, and there isn’t a way out. So I thought that addiction, from personal experience—and I hope and suspect more broadly—is a means for stasis, for preservation, after trauma. The rupture occurs, is not addressed, and a means for survival emerges in a form of addiction. Addiction is not your nemesis: it is your friend.

This assessment is reflected in kabbalah and the Matrix movies. Our entire world is a “holding pattern,” where we have the opportunity to change, yet most continually struggle. The ‘addiction’ that takes over can be materialism (as Brand later alludes to) or some other self-centered, damaging behavior. This preserves the ‘status quo’ as Brand and Peterson explain.

As we see in the Matrix, the answer is a higher consciousness of ‘knowing’ one’s true self, which in turn leads to the realization that one’s life is meant to be of service to others – as Brand earlier mentioned.

This is done via the path of correcting our attributes – the same emanations that make up the path of 12 Steps, the 7 Habits and the “path of the One” for Neo – which is really everyone’s path – he being the ‘example’ for others.

JP: Well, there’s certainly a literature on addiction that indicates that many people use addictive substances as a form of self-medication. They tend to find the drug that best medicates them, let’s say. For different people, that’s different drugs.

RB: Or even gambling.

JP: Yeah.

RB: One of the other things I’m proposing in my book—to use rather grandiose terminology—is that the template for recovery from obvious forms of addiction could be applicable to less evident forms of addiction, i.e. just patterns and habits.

This is an important truth in kabbalistic teaching. Both the problems and solutions appear together at all levels. Everything human beings encounter in this world is designed upon the same “Image of God,” which has become flawed through our own mistakes and has to be rectified through our own efforts. This includes the physical, emotional, intellectual and spiritual worlds within creation. Both the negative aspects of our patterns and habits, as well as their corrections, are formed around the same templates.

This goes back to the first mistake recorded in the Biblical narrative, where Adam and Even erred were then sent out on a path of correction – into the physical world we live in – our own ‘Matrix’ world, where the process of overcoming obstacles along our respective personal paths leads “back to the Source” – i.e. God.

JP: Yeah. Well, so far, the things you’ve laid out would be in keeping with that idea.

RB: Would they?

JP: Well, you admit to the problem. I think the idea of laying out your resentments is unbelievably useful, because that’s also a way of dealing with the malevolence within you that might interfere with your own recovery.

RB: Yes.

In our Knowledge Base, we discuss characters who are isolated from the central emanation of Tiferet, who fail to deal with their internal issues resulting in their inability to bring rectification to themselves. These include the Merovingian, Cypher and Commander Lock. Compare these to the characters who do seek that central sefirah of Harmony such as; Morpheus, Councillor Hamann and, ‘Kid.’ (See their respective Character Profiles.)

JP: If you’re angry at yourself, if you’re angry at your parents, if you’re angry at the world, the probability that you’re going to be in a mental state that’s going to allow you to chart a positive course for yourself is very, very low.

RB: How can you have a clear and authentic relationship with your wife, if you’ve not correctly understood what you feel about your own mother? If you feel like you were enmeshed or trapped in some way—if I’ve not understood that, if I’ve not gained a new perspective, if I’ve not transcended it by sharing it with another person…

JP: You see that in the Disney Sleeping Beauty story, when the prince is encapsulated in the castle, in the dungeon, at the end. Before he goes and rescues Sleeping Beauty, he has to go and confront his terrible mother. She turns into the dragon of chaos itself. He has to use honesty and truth to confront her. Until he does that, he can’t free the maiden from her sleep.

RB: Yes, yes.

All those ‘freed’ from the Matrix must confront the ‘mother’ which is the Oracle. Interestingly, she even describes herself similarly to Peterson’s “dragon of chaos,” with relation to the Architect:

Oracle: That’s his purpose: to balance an equation.

Neo: What’s your purpose?

Oracle: To unbalance it.

In each of the three movies, the Oracle speaks in challenging ways that are meant for Neo to resolve. Success comes via “honesty and truth” (=Tiferet) as Peterson states. As we explain, a hidden aspect to The Matrix is that all of the programs function in a way that ultimately benefits the humans.

JP: That’s called the “freeing of the anima from the negative mother archetype,” in Jungian psychology. It’s precisely that. That negative feminine will be overlaid on your partner, unless you’re able to clarify it, and clarify your relationship with it. That could be something like overprotection, like in your past—or it could be neglect, for that matter. Or it could be the rejection at the hands of many, many women, before you encounter this woman. You’re going to bring that bitterness forward, as a kind of projection.

RB: If we are unwilling to undertake this kind of excavation, then we are doomed to continually have relationships that are cutaneous. The superficial coordinates will govern our experience of relationships.

JP: Yes. That’s the repetition compulsion, from the Freudian perspective. That isn’t how Freud explained it; that’s how a Jungian would explain it. But the simple explanation of it is, well, if you bring the same set of unexamined presuppositions to every situation, the same fate will play out. You might say, “well, all those women are the same.” It’s like, “well, actually, no. But the part of them you’re able to make contact with acts the same every time.” That’s a very different thing.

RB: Brilliant. This is where six and seven, the next Steps, chronologically occur. Six, having done this inventory, you recognize what patterns have been at play in your life—which “defects of character have governed you:” often pride, wanting to control other people’s perspective, self-pity, self-centeredness, intolerance, impatience, greed, jealously, envy, lust, sloth.

This relates back to Neo’s training with Morpheus, where the latter kept ‘defeating’ him as they sparred. Morpheus stated that the problem was deeper than Neo’s ‘technique.’ It was a matter of “freeing his mind” from the same way of thinking that he approached each “fight sequence” with. Neo had to understand how to break the ‘rules’ and temptations that the Matrix system had in place – confining him within that false reality.

Peterson and Brand continue on this theme of the ‘trappings’ …

JP: That’s where you identify the seven deadly sins, and how they play out in your life, essentially.

RB: Yes. Step 6 is about becoming willing to live differently—saying, “are you actually willing to let go of lust? or do you like lust? do you like being impatient? does it serve you, in some way, to be slothful?”

“You have to let it all go, Neo, fear, doubt, and disbelief. Free your mind.” – Morpheus

JP: It’s highly probable that it does. It’s easy; it’s gratifying; it’s powerful; it’s pleasurable—especially in the short term. There are reasons that people are tempted by the seven deadly sins.

RB: They’re kind of glorious—they’re dark glory and beauty.

JP: Oh, absolutely. That’s exactly right. There’s a dark romanticism, and you really see that in the death of celebrities around 27. They fall in love with the allure of that romantic death, and it does them in.

RB: So the anti-libido; the dark libido; the death force. So once you have diagnosed which particular defects of character have been most prominent in your path, and become willing to let go of them, Step 7 is making a concerted and real effort to live without them.

Step 7 relates to the attribute of Netzach (see below) on the pro-active right side of the Tree of Life. It’s not by accident that over 50 of the Psalms in the Bible begin with some variation of the word “Netzach” with relation to the ‘orchestration’ of that which is written of in the remainder of each of those Psalms – which themselves are designed to bring correction and healing into our lives.

JP: That’s a sacrifice there, eh? That’s, “what are you willing to sacrifice, in order to move forward?” You have to give up something that you love, and you may have to give up the thing that you love best. That’s the fundamental sacrificial motif.

RB: Sacrifice is an unattractive idea in our society, that’s based on consuming and indulgence. This is again, perhaps, where you and I somewhat differ. Whilst this will not change about the individual’s engagement—a kind of Step 1 acknowledgement that there needs to be change—this is where I say there needs to be a social responsibility. For whatever reason, our society’s become a manifestation of these darker impulses. These are the prevalent forces, at least in the kind of society I live in.

JP: Too much emphasis on immediate gratification.

RB: Too much emphasis, because immediate gratification is a tool of consumerism. This would be my argument. But at this point in the program, the spiritual becomes—I find, personally—undeniable. You have to call to something else. You have to, in a sense, lay yourself open. The idea of prayer becomes quite important.

As mentioned earlier. Brand directly associates the consumerism of the world with addiction and pits it against spirituality. This directly relates to a saying in the gospels:

“No one can serve two masters, for either he will hate the one and love the other, or he will be devoted to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve God and money.”

With ‘money’ being equivalent to materialism/consumerism. The humans in the Matrix became enslaved by the machines due to their self-centeredness and lust for materialism. (3)

JP: So there’s a Jungian idea, there. The Jungian Self is the thing that guides the ego through transformations. Imagine the ego, which is what you think you are—well, the thing about the ego is that the ego can be wrong, and the ego can die and be reborn. What that indicates is that there’s something underneath the ego that can guide that process of transformation.

RB: Yes, yes.

JP: Partly what you’re calling on, when you call on this higher power, is—at least from the psychological perspective—a decision to rely on that thing that can guide you through transformation.

RB: Yes, because surely—as we said, in relation to another—we are likely relating to a set of coordinates that we impose on the female. The same would be true of the self: we have created an egoic impression; we have constructed an artificial self. But beneath it there is a higher Self, or an ulterior Self.

JP: That’s right. It’s often composed of things that you refuse to or weren’t willing to develop. So when Jung talks about, for example, the incorporation of the shadow—you’ve constructed an ego, and there’s things it can do and can’t do, that it’s allowed to do and isn’t allowed to do. Then there’s a shadow domain that consists of the things you could do, but haven’t. Some of that’s terrible, but some of it’s what you need to break free.

RB: Is there an infinite variety in the shadow, or is there sort of templates, there? Is there, would you say, a common component?

JP: Aggression and lust are the two, because they’re the two that are most difficult to integrate into the ego. Aggression destroys, and, of course, lust subsumes the individual to sexual desire.

RB: Lust is identified as a very powerful self; it can subsume; so I suppose that’s why a lot of theological doctrines focus on the control of lust.

Aggression, particularly when leading to murder (literal or metaphorical) is the direct antithesis to Tiferet. (Do not murder is the 6th of the ’10 Commandments’ as Tiferet is the 6th of the full set of 10 emanations.)

Lust relates in an opposite manner to Yesod, the sefirah of ‘connection.’ Note next how Peterson describes what it does to relationships. (See Step 9 – Yesod below and our profile on Morpheus as his life relates to connection and sexuality).

JP: Well, it’s a disruptive force. For example, if you make a medium- to long-term relationship with someone, and you negotiate that, that provides you with a stable structure that can operate across your entire life. It’s good for you; it’s good for them; it’s good for your kids; it’s good for society. But then, if you’re really attracted to someone momentarily, you can be driven to act on that. All the rest of that can burn up. So it’s no wonder that it’s viewed as a force of tremendous disruption. Now, it’s also a force of tremendous life, right? You want to be attracted to people; you want to have that vital libido as part of what’s driving you forward. But hopefully it’s on your side, and not working against you. If you’re successful, and you put yourself together, and you’re disciplined, you should still be maximally sexually attracted. But it should be under your control. You’re not the puppet of that force, anymore. It’s integrated into you, and that’s a much better way to manage it.

RB: In your understanding, how is the shadow incorporated? What rituals, what ceremonies, what behaviours successfully incorporate the shadow, say, using the example of lust? What’s a way back in for the lust that has been disembodied or repressed? What’s the safe way back in? Is there one?

JP: Well, I think part of it is to admit to your desires within your own relationship. You might say, “well, I’m tired of my wife.” It’s like, “well, yeah. Maybe—maybe you’re tired of the games that you’re intelligent enough to play with your wife. But she’s as pluripotent as you are.” You have to admit to your desires, let’s say, and maybe you have to make them consciously manifest within your own relationship.

RB: Hmm.

JP: People do that by dressing up, or by playing sexually, I would say.

RB: Yeah, play.

JP: Play is a transformative element.

RB: Yes.

JP: It might be that you’re uncomfortable with the idea of your wife as sexual plaything, because you think that a woman that’s married should be proper and prim, and should only behave sexually in a certain way, in which case—well, that becomes stale and dull, and you’re more likely to be tempted by something on the outside.

RB: To me, that’s a very obvious example of how habitualized thinking is prohibitive, even without reaching the extremes of self-destructive, addictive tendencies. If I have a habit of regarding my wife as Object A—even if that’s not objectification as we typically take it, but limiting beliefs about my wife—the tools that break down addictive thought patterns could be used to create new terrains, new liberty, new play. So once you’ve done up to Step 7—you’re right, it’s a sacrifice of the old self, and a handing over to some kind of sublime, divine Self. Step 8, you make a list of people you have harmed and become willing to make amends to them. So you look back and go, “oh, God—I shouldn’t have stolen that; I shouldn’t have done that; I treated that person badly; that was wrong; I lied.” So it’s moral; it becomes quite a moral process.

JP: That’s a real repentance and atonement. Atonement is “at-one-ment.” If you’re carrying transgressions that you regard as transgressions now, in your life, you don’t want to carry those forward. You want to step forward in life without that moral burden, because you’ll have contempt for yourself, otherwise, and you won’t take care for yourself.

NETZACH & HOD

Step 7. Humbly asked Him to remove our shortcomings.

Step 8. Made a list of all persons we had harmed, and became willing to make amends to them all.

YESOD

Step 9. Made direct amends to such people wherever possible, except when to do so would injure them or others.

As with the 7 middot and the 7 Habits, these ‘lower’ Steps are about relationships with others.

These next three emanations ‘mirror’ their counterparts above, but convey relevant detail to the plan of change. They are the final steps in bringing something into the world of ‘action,’ associated with Malkhut (kingdom/sovereignty).

Netzach and Hod are called the “wings of Yesod.” With regard to step 7, we proactively ask for help with our shortcomings (Netzach) and in Step 8, make a list (Hod). The aspect of Hod helps us determine what is correct or incorrect in attempting to make amends.

These two emanations resemble the earlier steps mentioned under Chesed and Gevurah, only now we’re moving things from the realm of thought into that of action and with the greater community.

We are now ready to take action to connect to others in a meaningful way. This is the synergistic and connective aspect of Yesod. Everything we have considered in Steps 1-8, now passes through Yesod and plays out in the world of ‘action’ below – Malkhut.

One of the typical parts of AA meetings is, if and when a person feels comfortable, they stand before the group and introduce themselves in a manner of, “Hello my name is __ and I’m an alcoholic.” This a key part of the fundamental philosophy of one person (alcoholic for AA) helping another. Many people are not truly prepared for what they need to do, but the community stays open for them to keep trying.

In The Matrix Reloaded, the character of Councilor Hamann acts in the mode of Netzach when he approaches Neo and discusses his own shortcomings with him.

Captain Niobe exemplifies a healthy attribute of Hod in her situational analytical ability, including her statement of placing her trust in Neo. Also without Hod functioning properly, a person can have “boundary issues” (such as the ‘exuberant’ character ‘Kid’ in The Matrix Revolutions film.)

RB: Also, in a sense, what you’re talking about is allowing lust back in—incorporating lust. This is a broader method for incorporating annexed aspects of the Self. Like, “how can I fully love myself, if I know I treated that person abominably?” Well, if I go back, and say “that was wrong; I did you wrong; I owe you an amends,” you invite that part of your life in.

JP: That’s right.

RB: You amend your path through life, as well as teaching yourself that is not the way we proceed anymore. That’s Step 8.

JP: That’s real action in the world. It’s not a hypothetical, at the point. It’s kind of like telling people what you’ve written down about your faults, because it makes it real when you’re acting it out with someone else. It’s not only a mental thing, at that point.

They now transition from the ‘wings’ of Yesod to the latter attribute itself. Yesod is the synergy of the analysis of the first 6 Steps and the detailed considerations of the next ones. It then “connects all of this” to the “world of action” in Malkhut.

RB: Step 8 is, “write up the list of people.” Step 9 is, “now go do it.” It makes the distinction, I think, to create a space for you where you’re not continually thinking, “I’m not fucking doing that; I’m not going to apologize; I was abused by them; fuck that—they did as much wrong as I did.”

JP: Right, which is not the point.

RB: It’s not the point.

JP: They might have done more wrong than you did, but you’re still stuck with the fact that you still did something wrong, and that’s not good.

RB: That’s right, and if you refuse to surmount the obstacle of some arbitrary measure of who is more wrong, then you continue to cast yourself in victimhood.

JP: That’s exactly right.

RB: You have no personal autonomy.

JP: It doesn’t matter if you’re only 5 percent at fault, and it also doesn’t matter if the other person apologizes to you. They should; it would be better for them; it might make things lay out. That’s not the point.

RB: This, perhaps, is where what I think is significant—now that your life has become not a negotiation between you and other beings as materially present themselves, but between yourself and a higher purpose that has been declared earlier, you are now operating on a spiritual plane. You are no longer about, “if I do that, I get that.” It precisely doesn’t matter if the other person goes, “I don’t care if you apologize or not. Fuck off.”

JP: In religious language, that would be expressed as the discovery of your Father in Heaven, instead of your earthly father. Your Father in Heaven would be the higher spiritual authority to which you owe allegiance. You can think about that either in religious terms or in nonreligious terms—what you’ve done is you’ve, in some sense, abstracted the idea of a higher authority and a higher purpose, and you’ve decided to devote yourself to that. That’s a religious act.

RB: That’s precisely antithetical to postmodernism: “there is an essence; there is a code; there is a way; there is a truth.”

JP: That’s right. That’s what is precisely antithetical. The postmodern claim is that there are multiple ways of looking at the world. That’s true, but the antithesis of that is, “yes, but just because there are multiple ways of looking at the world doesn’t mean that there are multiple proper ways of looking at the world.”

RB: Yes.

JP: In fact, there’s a very narrow range of proper ways of looking at the world.

RB: My concern with atheism has always been its sort of easy affiliation with nihilism: “oh, why don’t we just wander over there and start fucking people, then?” That’s where my mind immediately goes. If there is not an order, why not smash everything to smithereens? You’re saying, ideological, that is what’s happening. Ideologically, we are deconstructing God; we’re deconstructing morality; we’re deconstructing gender.

JP: That was the danger that both Nietzsche and Dostoevsky pointed to, clearly. You dispense with the transcendent principle, and you open up the landscape for impulsive nihilism.

RB: They responded to post-enlightenment rationalism. Is that what Dostoevsky and Nietzsche were responding to?

JP: They were responding to, essentially, the idea of the death of God. Both of them, and explicitly.

RB: Is that an enlightenment idea? Where is the death of God happening prior to Nietzsche?

JP: At the hands of a kind of arrogant and narrow rationalism and materialism.

RB: Exponentially, that has led us where we’re going now, which is a kind of digging the earth from beneath our feet, putting ourselves into the abyss.

JP: That’s right. That’s the hypothesis, precisely.

MALKHUT

Step 10. Continued to take personal inventory and when we were wrong promptly admitted it.

Step 11. Sought through prayer and meditation to improve our conscious contact with God, as we understood Him, praying only for knowledge of His will for us and the power to carry that out.

Step 12. Having had a spiritual awakening as the result of these Steps, we tried to carry this message to alcoholics, and to practice these principles in all our affairs.

Steps 10-12 reflect the left, right and center aspects in a similar manner to Step 1. We continue to inventory (an aspect of the left), pray and meditate (the center column of harmony) and take active steps to share with others (the proactive aspect of the right)

This final grouping of Steps 10-12 are synonymous with the 7th of the 7 Habits – “Sharpen the Saw.” We have to continually refine and move forwards. Stagnation is not an option as our environment will change and we need to constantly be on guard against any forces (internal or external) that can cause us to stumble. This is the motto of “One Day At A Time.” found in AA literature.

RB: The last three Steps. Step 10 is, like, “continue to make inventory. Let this process continue.” For me, in psychoanalytic terms, it’s like when there’s a moment—I know any spike in my energy: if I go, “oh, I felt something. That was interesting. I felt jealous, there. I felt small, in that moment.”

JP: Exactly.

RB: These are the moments I know. “How was I participating in that? What belief of mine was being challenged? Is that a helpful belief?” “Belief” being a thought that I like having.

JP: Right. That’s a kind of consciousness: “well, I’m going to fall apart. I’m going to make mistakes. I don’t want to make mistakes. I’m going to keep an eye out for when I do make mistakes, and I’m going to make them conscious. And then I’m going to try to work on them.”

RB: Yes—”bringing them into consciousness.” My number one fear on a personal level, and possibly on a social level—I don’t quite know how to extrapolate or conflate those two notions—is unconsciousness. I get very afraid when I’m dealing with unconscious individuals—when people don’t know why they’re doing what they’re doing. You might see this in violent rage, or in less dramatic or theatrical behaviour.

JP: Yeah. There’s a great idea that lurks at the bottom of the Christian mythological tradition: a little bit of consciousness destroyed the original paradise. We became conscious enough to be aware of our own mortality. The cure for that is way more consciousness, not a return to unconsciousness.

RB: Yes. There’s no going back. I sometimes think the plethora of zombie movies is, you know, “they don’t know they’re already dead!”

JP: That danger of the zombie is the danger of the desire for unconsciousness, as a solution to life’s problems.

RB: I think, again, this something we are being invited to participate in, through consumerism: to live your life continually on the frequency of unconscious energy, such as desire and fear. We’re not being invited to participate on the level of conscious interaction, presence in the moment.

JP: Well, you could make that case if you made the case that consumerism promotes the gratification of immediate desires, above all else.

RB: I think it does. That’s what I’m pushing for. With this original sin, a little bit of consciousness is a dangerous thing. We become aware of our vulnerability and mortality, our nakedness, our corporeal nature. But the solution to this is…

JP: To become more conscious.

The solution both Peterson and Brand arrive at is to become “more conscious” and escaping the gratification of immediate desire. This is also the main overarching theme of The Matrix movies as we discuss in another article.

(Our portion of the transcript ends at 44:21. The entire transcript is available here: https://www.jordanbpeterson.com/transcripts/russell-brand-2/

- In the kabbalistic tradition, the seven lower sefirot are associate with seven Biblical figures. Beginning with Chesed they are; Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, Aaron, Joseph and David. The two representing attributes from the left/restrictive side, Isaac and Aaron, have the least written about them in the narrative yet play critical roles based on aspects of ‘restriction.’

- All the sefirot relate to different names and terms used for God. Tiferet is associated with the ‘most holy’ 4-letter name (spelled Yod-Hey-Vav-Hey) and with the powerful expression, “The Holy One, blessed be He.”

- The back story to where the first Matrix movie begins is found in supplementary Matrix materials including The Animatrix film.

“We can only break through the vise grip that mechanistic science has on our consciousness by recognizing the role of God in everything. The Baal Shem Tov, founder of Hasidism, taught that no leaf falls without God’s willing it. Each of us experiences amazing events—from coincidences to clear miracles—in our lives. We must see the Divine acting in all these and have the courage to tell those stories. When we do, we will see that the billiard-ball causation of the old mechanistic science is not the only force in the universe. God is in our midst, with the force of cohesion rather than mere causation, bringing people and events together for an ultimate good. “God sent me before you.” (As Joseph told his brothers – Genesis 45:5)

― The Gift of Kabbalah: Discovering the Secrets of Heaven, Renewing Your Life on Earth