Last Updated 1.28.24

In our first background article we made reference to concept of “pre-existence” — when there was a pure singularity that we can only refer to the “transcendent aspect of G-d.” We do not directly relate to G-d at this level. This is not to say however that there is no ‘connection.’ One was enabled within the most unique place on earth – the Holy of Holies. But what is the connection between this and Shir Hashirim? The story moves back & forth along the longing of the past, to the exile of the present, to the hope of an even better future. Some verses have simultaneous positive and negative connotations. Opposites can exist in the same place. Shir Hashirim takes us to the Holy of Holies where every aspect of existence is one with the transcendent.

Kodesh HaKodashim

The Temple served as a type of connection between Israel and Hashem. Even the terms associated with it, reveal this. The word for offerings, ‘korbanot,’ from ‘karev,’ means to “come near.” That for incense, ‘ketoret.’ from ‘katar’ (Aramaic) means ‘connection.’

The term “Holy of Holies” (Kadosh Hakadoshim) is a reference to the inner and most sacred space within the Temple described in the Bible. At this “highest level within existence,” the High Priest would make the connection between the people and G-d “outside of existence.” (1)

Here there was a ‘joining’ of our limited view/connection relating to the ‘immanent’ aspect of God (from within the binary nature of existence) with the transcendent aspect of the Creator, where everything is ‘singular’ and there are no aspects of distinction or conflict. This is often referred to as “Ein Sof,” meaning “without end.”

This concept, that the Holy of Holies is a place connecting our multi-dimensional world to the “eternal-singular,” is what lies behind this remarkable statement where Rabbi Akiva draws a connection between the Holy OF Holies and the Song OF Songs:

“Heaven forbid that any man in Israel ever disputed the sacredness of Shir HaShirim for the whole world is not worth the day on which Shir Hashirim was given to Israel, for all of the Writings are kodesh (“holy”) but Shir Hashirim is kodesh kedashim (“holy of holies”).”

Rabbi Akiva, Mishnah Yadayim 3:5

On the surface, this statement seems outrageous. Rabbi Akiva says that all the books of the Hebrew Scriptures are holy, but Song of Songs is the holiest of them all. What about the books of Moses? The prophets? The Psalms?

Akiva is of course, a well-respected source. Clearly there is something unique about this text. It’s time to think out of the box. Perhaps a few boxes.

Imagination

But all of this is a far-reaching plan, the Lord’s plan to perfect the imaginative faculty, for imagination is the healthy basis for the supernal spirit that will descend on it … the supreme divine spirit destined to come through King Messiah. Therefore, now the imaginative faculty is being firmly established. When it is completely finished, the seat will be ready and perfect for the supernal spirit of the Lord, fit to receive the light of the divine spirit, which is the spirit of the Lord, a spirit of wisdom and understanding, a spirit of counsel and strength, a spirit of knowledge and awe of the Lord.

Rabbi Abraham Isaac Hakohen Kook, “Orot” (1920)

“Imagination” does not mean a lack of boundaries. The latter exist in terms of eternal truths and principles that reflect the Creator and creation. Just as a top athlete might display imaginative skill within the ‘rules’ of their sport, the same applies when pondering spiritual realities.

The difference, however, is that with the spiritual, the more you progress, the more you will be able to bend, and in a sense, even ‘break’ certain rules. Of course, even the idea of ‘breaking rules’ is in appearance only, as this is itself part of the rules, or ‘framework,’ of reality.

This is similar to the midrash of the moon and sun mentioned in the previous article. G-d did not make a ‘mistake’ when He ‘diminished’ one of them. It was all part of the plan leading to an endpoint.

What we have in studying any Torah text is a dynamic relationship, involving at one end the expansiveness of imagination, and at the other, the restrictiveness of the words and their established context. What is especially interesting with Shir Hashirim is not only that it is more mysterious than any other, but also that the text itself is about the dynamic of masculine ‘force’ and feminine ‘form.’

Not only is imagination ‘healthy’ (as said in the ‘Orot’ quote above) and needed to study this text, our collective imagination, in the highest world of existence, the unified level of Atzilut (Atzilus), is far greater than the sum of us individually. (See ‘Interpretations’ below.)

There is a direct relationship between the Shekinah and this level (of understanding):

The Shekinah has been told at this hour, “Go and reduce yourself,” and is lowered to the worlds of Briyah, Yesirah and Asiyah (Creation, Formation and Action). These spheres are beneath her dignity; the honor due to the King’s daughter really belongs in the Sefirot of Atzilus.

Tikkun Shechinah, Reb Moshe Steinerman

Further, the Shekinah (who is called among other names, the Divine Daughter, and Sefirah of Malkhut) the key figure in Shir Hashirim, is constantly revealing secrets to those seeking. This is found in the writings of one of the earliest kabbalists, Moshe Cordovero:

Cordovero describes the Daughter of the King, namely the last Sefirah, as flowing and innovating secrets all the time, namely, also in the present, as we learn from the tense of the verbs.

The Privileged Divine Feminine in Kabbalah, Moshe Idel

The key is two or more people studying together and discussing matters can provoke each other to think in ways they normally might not have:

When two sit together and words of Torah pass between them, the Divine Presence (the Shekinah) rests between them.’

Mishnah, Avot 3:7

This is why this project is a collective effort, open to anyone with concepts or citations to add to the study portion, or ideas for anything related to what we are doing and how we are going about it. (As an example, someone suggested we use AI technology to come up with new ways to approach the study or connect it to things in this world!)

All of that being said, Song of Songs will also stretch our own imagination in new ways. It is a text where opposites exist ‘together’ and must be resolved. This includes verses simultaneously having “positive and negative” connotations, that span and intermingle past “good times,” a present exile & process of rectification, and future redemption.

Back to the Temple …

Interpretations

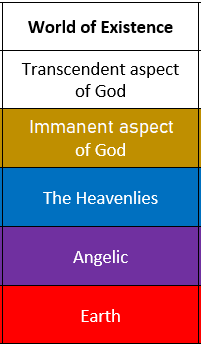

The temple mount follows a design based on what are called the four Worlds of Existence. These are embedded in this verse:

Everyone that is called by My name, and whom I created for My glory, I formed him, yea I made him.

Isaiah 43:7

Prior to these four worlds is the ‘unknown’

- The ‘essence’ of, or transcendent aspect of the Creator beyond our existence, the mind or desire or will of G-d.” This is not one of the [four] Worlds of Existence but considered “pre-existence,” or pure ‘singularity’ — before any ‘thing’ existed. This is what the Temple and High Priest are concerned with.

- Atzilut (Nearness) = The Holy of Holies, collective consciousness, the interface, the “Image of G-d,” or ‘immanent’ aspect of G-d that we relate to. Here’s the High Priest would ‘connect’ to that “beyond existence.”

- Beriah (Creation) = The Holy Place, the world of the heavenly Temple, height of personal consciousness. The world of governing forces or powers.

- Yetzirah (Formation) = Court of the Brazen Altar, the angelic world, Jacob’s ladder (in his dream of Genesis 28:10-17).

- Asiyah (Making) = Outer Court(s), our ‘physical’ world of concealment.

The world of Atzilut, the beginning of a unique existence separate from the pure singularity (yachid) before it, is one of composite unity (echad). What was ‘undefined’ within “pre-existence” before this, emanated into Atzilut. This is similar to sefirah of Chokhmah/Wisdom, which came from ‘nothing,’ as discussed in the previous article. (2)

NOTE: A concept regarding the Worlds of Existence is that each world is ‘understood’ via that world below it. The higher is also the ‘essence’ of the one that comes after it. From what we find in Atzilut (via the Image of G-d) we can gain some insight toward the mind of Hashem.

This is why the world of Atzilut is called an ‘interface’ between the unknowable aspect of G-d and worlds within Creation. The G-d appearing in the Genesis creation text, called ‘Elohim,’ is the aspect of G-d within existence, that we can read about, discuss, pray to, etc. (3)

Atzilut reflects the idea of multiple things within a single point. From that point would come everything into what the Bible calls Creation (Beriah). Think of it like the scientific idea of the point before the “Big Bang.” This hints that everything that would ever come into existence was ‘present’ with Hashem, before any of it had its own identifiable identity in Atzilut.

This goes beyond physical things. It includes the interpretation of verses and of texts of the Bible. Thus, there is more than one way of understanding Shir Hashirim. However, all are grounded in the same framework of spiritual reality.

Shir Hashirim takes us into Atzilut, the Holy of Holies of the Temple, and makes a connection beyond existence, similar to the High Priest. This makes Shir Hashirim an ‘interface’ for all other texts and learning!

The parameters (sefirot) of Atzilut are not completely limited. Each of them can go on endlessly. Each of them has a level of abstract dimensions … that still has an element of Ain Sof within it. It’s love that can go on endlessly. That’s the beauty of interface of Atzilut, It allows us that bridge, It’s on our terms but is infinite vision. Infinite love.

Ayin Beis, Existence Unplugged, Chapter 5: Atzilus, Rabbi Simon Jacobson

The main areas of interpretation center around the two main characters in the text, one masculine and the other feminine.

The most common ideas relate to these concepts:

- Man and Woman

- G-d and the “Children of Israel”

- G-d and the Human Soul

1. Man and Woman

At first glance, Song of Songs seems to be a dialogue between a man and a woman, lovers who admire one another, but who lost and seek to find each other. It is also quite ‘sensual.’ In the first chapter alone, there are references to touch, taste, sound, sight, and smell.

This more ‘literal’ level of understanding presents an array of difficulties.

- Why is such a text in the Bible? It does not seem to relate to anything relevant that we find elsewhere, such as commandments, prophecy, morals, ethics, or even history.

- If we are going to use verses, such as 8:4 (“awaken not love before its time”) to promote virtues such as celibacy until marriage (as some do), why then does the book contain such ‘erotic’ language leading up to that?

- What about these same ‘lovers’ also being referred to as brother and sister as we find in the text? Something does not add up.

Trying to make sense of Shir Hashirim in some literal sense, has been a known issue for centuries:

The emergence of peshat or “plain meaning” literal exegesis in early medieval Jewry was problematic when applied to the Song of Songs. Unlike any other part of Scripture, here an explicit rabbinic stricture was in force against reading the text in accord with its plain meaning. Perhaps for this reason both the commentary attributed to Sa’adya Gaon (tenth century) and RaSHI (eleventh century) offer versions of the historic allegory in their commentaries, unlike their writings on other books of the Bible, where they permit themselves, to one degree or another, to leave rabbinic tradition behind and to seek out the plain meaning.

Shekhinah, the Virgin Mary, and the Song of Songs: Reflections on a Kabbalistic

Symbol in Its Historical Context, Arthur Green

It is evident that such a rendering of the text causes more problems than it solves. Thus, the consensus is that the text is allegory.

There is even a comment in the Talmud, saying that the text ‘hides’ the deeper meaning and to simply read it plainly, is to make a mockery of it:

He who recites a verse of the Song of Songs and treats it as secular air, and one who recites a verse at the banqueting table unseasonably, brings evil upon the world. Because the Torah girds itself in sackcloth, and stands before the Holy One, blessed be He, and laments before Him, Sovereign of the Universe! Thy children have made me as a harp upon which a clown plays.

Sanhedrin 101a

One source divides the ‘audience’ into three groups. Those who read it like heathens, those who read it correctly, and those who go further into the spiritual connections it provides — which is at the heart of our Shir Hashirim Project:

I have observed that concerning the Song of Songs there are three classes of individuals with three distinct sets of opinions. The first group, possessing neither understanding nor insight, has left the world scattered with corpses. They contend that its words are those of sexual desire, seductive enchantment and falsehood, vanity lacking all value. Let their mouths be stuffed! Their eyes blinded! For if their words were true, it would not have been composed among the works of Scripture nor counted among them

The second group views it as an allegory of the love of the Creator, the God of the entire world, for the splendor of Israel, His special treasure and unique inheritance, comparable to the desire of the lover for his beloved, of a man for his wife. They have established their words, suggested their interpretations in accord with this allegory.

The third group, those who receive Shekinah, who possess a portion in God’s Torah and remember it well, the true wise men of Israel who have revealed its secrets and hidden mysteries, who have brought forth its supernatural depths through wisdom’s path and knowledge, have interpreted the entire text with that pithy principle enunciated by our sages in the tractate on Oaths: “Every Solomon mentioned in the Song of Songs is holy,” referring to Him who is the possessor of peace, referring to Him who is the possessor of peace, save one: ‘I have my own vineyard: You may have the thousand Oh Solomon.”

Ezra ben Solomon of Gerona, Commentary on the Song of Songs

This is not to dismiss the idea of love between a man and a woman. There’s an interesting verse in the Talmud that makes such a comparison, expressing the deep love God has for the people in a way they could relate to:

Whenever Israel came up to the Festival, the curtain would be removed for them and the Cherubim were shown to them, whose bodies were intertwisted with one another, and they would be thus addressed: Look! You are beloved before God as the love between man and woman.

Yoma 54a

Song of Songs is unique among literature in this respect.

A key distinction between the Israelite and pagan portrayals of Divine love is that no pagan culture spoke of a god as a husband or a lover of his people. Israelite religion, in its radical monotheism, demanded the people’s absolute fidelity to the One God. In human terms, there was only one relationship that reflected that kind of fidelity and that was a woman’s vow of loyalty to her husband. From Amos to Ezekiel, the prophets described infidelity to God as adultery, promiscuity, sexual laxity, and prostitution. Israel, in its covenant with God made on Mt. Sinai, was “married” to God. God, as the husband, was explicitly jealous of any infidelity on the part of His wife. Religious fidelity is described in the terms of marital fidelity.

Why Do We Sing the Song of Songs on Passover, Benjamin Edidin Scolnic

We will move on to the major allegorical interpretations.

2. God and The Children of Israel

The same text provides a nice segue into this second and major perspective on Shir Hashirim.

The prophets may have denounced infidelity, but the Song of Songs spoke of reunion and love, the kind of love that the believing rabbinic Jew felt for God. Even the Psalms do not talk about God as the lover or bridegroom of Israel. The Song of Songs is seen as a dialogue between God and Israel, and this provides the book with a unique religious intensity.

Why Do We Sing the Song of Songs on Passover, Benjamin Edidin Scolnic

This is considered the primary interpretation of the text, with application to the others (as is the case with many things in Torah learning).

As mentioned, Shir Hashirim has verses with multiple, if not ‘opposite’ meanings, that are both true:

Rabbi Yishmael, how do you read the following verse in the Song of Songs (1:2)? Do you read it as: For Your love [dodekha] is better than wine, or as: For your love [dodayikh] is better than wine? The first version, which is in the masculine form, would be a reference to God, whereas the second version, in the feminine, would be a reference to the Jewish people. Rabbi Yishmael said to him that it should be read in the feminine: For your love [dodayikh] is better than wine. Rabbi Yehoshua said to him: The matter is not so, as another verse teaches with regard to it: “Your ointments [shemanekha] have a goodly fragrance… therefore do the maidens love you” (Song of Songs 1:3). This phrase, which appears in the next verse, must be describing a male, and therefore it can be deduced that the preceding verse is also in the masculine form.

Avodah_Zarah.29b.8 (Sefaria.org)

When discussing any dynamic involving God and humans, (i.e., prayer, meditation) the masculine aspect relates to the Divine and the feminine to the human. The above text also shows how tricky the text can be in places, regarding who is speaking to who.

The most common understanding is that our text is a song of love describing the intimate connection between God (the masculine voice in the story) and the “Children of Israel” — the descendants of Jacob, who was also named Israel.

The feminine voice in the story ‘represents’ the people but is also that of the ‘Shekinah’ — the divine presence who is with the people. The explanation for this is that the Shekinah relates to both, shachen, which is a ‘neighbor,’ and to shochen, meaning “to dwell within.”

This adds another interesting dimension to the text of Shir Hashirim, as it seems that the Divine Presence itself is “in need of correction,” and though she “accepts this,” she also relates that her present exile was due to the actions of the people.

In the Biblical narrative, God forgave Israel for the sin of the golden calf (a subject that is alluded to in chapter 1) and eventually brought them into the Land of Israel, where they continued to go astray. His patience (seemingly) exhausted, He finally sent them into Exile.

Through the voice of the Shekinah in Shir Hashirim, she/they express longing for the return of their earlier intimate status, in the Land of Israel. However, when the male figure approaches her, she suddenly forgets her earlier resolution. (A very ‘human’ behavior!)

In the text of Shir Hashirim, when the female seeks out the male to reunite, he will not accept her without her first correcting her mistakes and returning to her “true self.” This is the concept of “teshuvah” (return). The goal of this return is the “Image of God” we are created in.

HARK! MY BELOVED KNOCKETH: by the hand of Moses, when he said, [And Moses said:] Thus saith the Lord: About midnight will I go out into the midst of Egypt (Exodus 11:4). OPEN TO ME. R. Jassa said: The Holy One, blessed be He, said to Israel: My sons, present to me an opening of repentance no bigger than the eye of a needle, and I will widen it into openings through which wagons and carriages can pass. R. Tanhuma and R. Hunia and R. Abbahu in the name of Resh Lakish said, It is written, Let be and know that I am God (Psalm 46:11). Said the Holy One, blessed be He, to Israel: ‘ Let go your evil deeds and know that I am God. R. Levi said: Were Israel to practice repentance even for one day, forthwith they would be redeemed, and forthwith the scion of David would come. How do we know? Because it says, For He is our God, and we are the people of His pasture and the flock of His hand. Today, if ye would but hearken to His voice. (Psalm 95:7) R. Judan and R. Levi said: The Holy One, blessed be He, said to Israel: Let go of your evil ways and practice repentance even for a flash and know that I am God.

Midrash Rabbah Shir Hashirim 5:3

The consequences of Israel’s transgressions have been devastating for the Jewish people and their connection via the Holy of Holies. The Temple was the more permanent ‘upgrade’ of the original portable Tabernacle (Mishkan) of Moses’s time.

There is a direct correlation between the structure and the Shekinah (divine presence). If one ‘went,’ the other followed:

This quality (of righteousness) is also referred to as Shekinah (dweller) and she has dwelled with Israel from the building of the Mishkan onwards, as it has been written: “And let them make Me a sanctuary v’SHaCHaNti (that I may dwell) among them.” (Exodus 25:8) … “When Israel sinned, the Shekinah fled, and the Temple was destroyed.”

Sha’are Orah (gate 1) Rabbi Yosef Gikatilla

The mystery behind this is that the Temple was designed intimately around the Shekinah:

What did David do? He readied silver, gold, copper, iron, wood, onyx, precious stones for setting, bright gems, embroidery and many other expensive stones, although, for the most part, the stones were onyx. He arranged the whole plan, the Sanctuary, its houses its stores, its stairways, the rooms, the Temple court, the hall, the shrines, the rest of the Temple’s plan, its courtyards and its chambers — all information he received through the holy spirit; the size of every place, the measure of all the silver, gold, the precious gems and any other measurement he required whether it be weight, size or shape. Everything was arranged in concord with the system and in accord with the Shekinah’s needs. As it is written, “David gave his son Solomon the plan …” (1Chronicles 28;11-19)

Sha’are Orah (gate 1) Rabbi Yosef Gikatilla

The good news is that during all the time of her exile, He watches over her, from “behind the wall, gazing through the window,” (v. 2:9) and protects her from her enemies.

A further example of the significance of Song of Songs as it relates to Israel and deeper concepts is found in the very opening words of the Zohar, the preeminent text of the mystical dimension of Torah. Commenting on Genesis 1:1, the Zohar goes straight to Shir Hashirim:

Rabbi Hizkiah opened his discourse with the text: As a rose among thorns, etc. (Song of Songs 2:2). ‘What’, he said, ‘does the rose symbolize? It symbolizes the Community of Israel. As the rose among thorns is tinged with red and white, so the Community of Israel is visited now with justice and now with mercy; as the rose possesses thirteen leaves, so the Community of Israel is vouchsafed thirteen categories of mercy which surround it on every side.

Zohar 1:1

3. God and Our Souls

Over thirty years ago, the Lubavitcher Rebbe announced to us … that the state of geula (redemption) had arrived …We had achieved a changing of the fabric or reality. Those limitations that formerly applied to what we could achieve we were in this world in a body – what could be healed, what we could hope for — all those caps were off. Everything was and is on the table for us.

Ani Lipitz

Ultimately, Song of Songs is about healing. Thus, a key understanding is about the connection between God and the soul, which is on a mission in this world, and longs to return from where it came.

Our world is one of ‘concealment,’ where the reality of God is not so easy to perceive. This is referred to as “Hester Panim” – hiding of the Face. Not only that but there are many barriers and distractions to “finding our way back,” making this quite a struggle at times. All of this, what we perceive to be “good and bad,” is from the Creator of course.

The cause of this separation goes back to the Garden of Eden story. The wonderful harmony of that existence was interrupted by what may be understood as an act of self-centeredness. Humans were “brought down” into the lowest world of existence where physicality was dominant. This remains the case to this day. The spiritual entity of the human soul was forced into this exile.

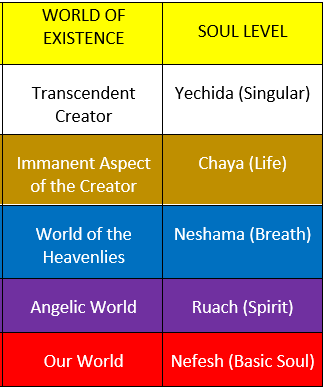

The concept of the soul in Torah, is ‘multidimensional’ in that it is understood to have five distinct ‘levels.’ These five levels correspond to the four levels of existence plus one of singularity, mentioned above,

Here we present a basic understanding, from the basic to the most advanced level:

NEFESH (SOUL): This is the ‘basic’ level of the soul. There are two aspects to the Nefesh that struggle against each other. One is about self-preservation and self-gratification. This is the soul concealed within a shell (klippah) within our present existence. It is not inherently good or bad, but its ‘tendency is toward “physical existence” and materialistic pursuits. Much of humanity never goes beyond this level. The other aspect transcends physical existence and has the ‘spark’ within it to “search for more in life.” This gives us the ability of effecting change within oursleves and the world. Relating to Torah understanding, this relates to the level of ‘Peshat,’ or the ‘plain meaning’ of the text.

RUACH (SPIRIT): Sometimes things happen that cause a person to contemplate spiritual matters and they begin to investigate. This is the soul level of Ruach. Here, a person may question, struggle, advance, stagnate or even retreat in their spiritual life. It is associated with our emotions and also with dreams (which “run between” the Nefesh and Ruach.) The Ruach level corresponds to the angelic world of existence in Jacob’s “ladder dream.”

Related to Torah understanding, the is the level of ‘Remez,’ or what the text ‘hints at,’ beyond the plain meaning.

NESHAMA (BREATH): This is where someone makes a true connection with spirituality – something “beyond the physical and emotional aspects of creation.” This is also where they begin to understand the choice they made in terms of their “mission in life.” This is also associated with reaching a level of personal consciousness. The Neshama relates to the beginning and highest world of ‘Creation.’

For Torah study, this is the level of Drash (Midrash) which pulls together different concepts. (An equivalent English term would be ‘homiletical’)

CHAYA (LIFE): This fourth level of the soul is very distinct from the first three. It has to do with a deeper change in “consciousness” – one beyond individual selves. This involves a spiritual relationship and sense of responsibility to others – beyond personal consciousness. Chaya is a level of collective consciousness. This relates to the VERY different world of existence before the actual creation. One could compare this to the first few words of Genesis, “In the beginning Elohim…” which, as mentioned, relates to the Image of G-d (B’tzelem Elohim). This is a world of “composite oneness” or ‘echad’ that ‘reflects’ (within existence) the pure singularity of “only God.”

This corresponds to the level of Kabbalah in study, which is where we go ‘beyond the text’ to see what relates to what and how Hashem runs things. As mentioned on the home page, kabbalah is the “science of correspondences” and is critical for understanding of Shir Hashirim.

YECHIDA (SINGULAR): Finally, the uppermost aspect of the soul is completely distinct from the others. Whereas they are seen as individual levels, Yechida is the essence of the soul, transcending and permeating all. In this way, it resembles the simple non-composte oneness of “pre-existence.” Yechida is associated with total self-lessness (called ‘bittul’) and unity with the Creator. It is also called the “essential idea of mashiach.”

This is also the ‘overarching’ level of Torah called Chasidus, which “runs through” the four other levels, but does not ‘mix’ with them, or as they mix with one another. It is like oil to water, which we will discuss in Chapter 1 notes.

This chart shows the correlation between the worlds of existence (behind the Temple design) and soul levels — our path of return:

Shekinah and the Soul

The soul is never “cut off” from G-d. It maintains a connection from this lowest and darkest world of existence, back to the ‘source’ – before existence (Ein Sof, as mentioned earlier). As with the High Priest, our place of connection is at the highest level of the soul within existence, called Chayah, meaning ‘life.’ This corresponds to the world of Atzilut. (4)

The following text relates to this and also connects this allegory to the previous, linking the Shekinah to the soul:

The text of the Tanya (Likutei Amarim) gives an analogy that when a rope has one end tied above, tugging at the lower end will draw down the upper end as well. The upper extremity of a soul is likewise bound to its source in the blessed Ein Sof, while at its lower extremity, it is enclothed in the body. When the lower extremity of the soul is dragged into spiritual exile through wrongful action, speech, or thought, this has a corresponding effect upon the upper reaches of the soul which are bound Above. In a sense, that ‘divine presence’ within us is also dragged into the separation. This is the esoteric doctrine of the “Exile of the Shekinah.” Sin causes the soul to be exiled within the ‘darkness’ of our physical world. The presence of God is not easy to see around us. This idea of the elements of creation ‘hiding’ God, is called the domain of the kelipot – a term meaning shells or barriers. Breaking through or free of these barriers goes back to what was said earlier about making connection to God through prayer (which includes deeper meditation), Torah study (like we are doing here) and mitzvoth, acts of kindness – which elevate his soul, enabling it to reunite with its source, the eternal, called Ein Sof, meaning ‘without end.’

Tanya (Likutei Amarim) ch. 45, Chabad.org

Prayer is the work of the soul. The first prayer of the day in Judaism, said upon the eyes opening, is the Modeh Ani. It is unique of all prayers, as it is addressed to G-d “outside of existence,” thus no name for Him is used. Only the term ‘king,’ which relates to Keter/the crown, which represents the realm beyond existence:

מוֹדֶה אֲנִי לְפָנֶיךָ מֶלֶךְ חַי וְקַיָּם, שֶׁהֶחֱזַרְתָּ בִּי נִשְׁמָתִי בְּחֶמְלָה. רַבָּה אֱמוּנָתֶךָ

Modeh anee lefanecha melech chai vekayam, she-he-chezarta bee nishmatee b’chemla, raba emunatecha.

I offer thanks to You, living and eternal King, for You have mercifully restored my soul within me; Your faithfulness is great.

This places the Modeh Ani at the same ‘level’ (Atzilut/Chaya) as Shir Hashirim — Kodesh HaKodashim, the “Holy of Holies” as it is called. It is the interface connecting everything in our existence below, to the unknowable and eternal above.

What a ‘precise’ way to start the day — back to our Source! (5)

Finally, as we see in the above allegories, physical imagery is assigned to G-d in the form of bodily and other spiritual elements. It is understood that Jewish mystical literature that comes under the heading of Shi‘ur Komah (“Measurement of the Body”) has its origins in Song of Songs.

This is not exclusive to our text, however. For instance, G-d presents “Himself” as a woman in Numbers 11:12:

Did I conceive this entire people? Did I give birth to them, that you say to me, ‘Carry them in your bosom as the nurse carries the suckling,’ to the Land You promised their forefathers.

We will develop all of the concepts mentioned in our study of the text itself. A key to Shir Hashirim is that though there are different ways to approach various sections, verses, and words — all of them connect us to the singularity – from the place of the Holy of Holies.

Thus, as we work on this project, we should also be seeking the deeper understanding we will need:

Let the King bring me into His inner chamber.

Shir Hashirim 1:4

NOTES

- For advanced study of Atzilut as the interface, see Ayin Beis with Rabbi Simon at https://www.chassidusapplied.com/ayin-beis/

- There are two main ‘templates’ in Torah regarding to the framework of existence. One is the four ‘worlds’ of existence and the pre-existence before it. (This will be addressed further in notes to 1:3,4.) The other is the ten sefirot, which exist in all four of these worlds. However, there are specific relationships between certain sefirot and particular worlds as follows:

WORLD – DOMINANT SEFIRAH

Pre-Existence (Ein Sof) = Keter

Atzilut (Nearness) = Chokhmah

Beriah (Creation) = Binah

Yetzirah (Formation) = Ze’ir Anpin (the 6 sefirot from Chesed to Yesod)

Asiya (Making) = Malkhut - For a fascinating insight, see Professor Daniel Matt’s 3-minute video, “In the Beginning, God Was Created”

- The relationship between the Worlds of Existence and levels of the soul:

WORLD – SOUL LEVEL

Pre-Existence (Ein Sof) = Yechidah/Singular

Atzilut (Nearness) = Chaya/Life (the level of collective consciousness)

Beriah (Creation) = Neshama/Breath (the highest level of personal consciousness)

Yetzirah (Formation) = Ruach/Spirit (the level of struggle and development)

Asiya (Making) = Nefesh/Basic Soul - For an excellent and concise (3-minute) look at the idea of the immanent and transcendent aspects of the Creator, see “In the Beginning God Was Created” by Daniel Matt.

How you can take part in the Shir Hashirim Project!

At the moment (before dealing with the text) we have four “background articles.” As people contribute more information and ideas, there may be more articles, including breaking up these four into separate pieces. This is the first phase of the project.

- Read the four background articles, then read the text of Shir Hashirim (or the other way around) to see what thoughts come to mind.

- Use the search terms (below) and your imagination to find relevant ideas.

- If something connects to anything you have read, or videos you’ve seen, send us the link with what to look for. Please state where the specific reference is in the article/video as time does not permit long reads/views.

- If what you are thinking of is an original concept or theme, write to us here or visit our Facebook group to post, and explain what you are pondering and we will go from there!

- OUR EMAIL: info@Matrix4Humans.com

- FACEBOOK: www.Facebook.com/groups/Devekut

KEY SEARCH TERMS FOR THIS ARTICLE: Holy of Holies, Temple, Worlds of Existence, Atzilut, Cohen, Hagadol, High Priest, Israel, tikkun, kadosh, interface, father, abba, Ein Sof, Shekinah, Children of Israel, soul, prayer